Levinas's AGI

Ethics Before World-ology

I’ve been returning quite a bit lately to Emmanuel Levinas’s claim that ethics precedes ontology, and what this might mean for how we build AGI systems.

For those unfamiliar, Levinas’s central claim is that our ethical relation to the Other comes before any theoretical understanding of Being. The encounter with another person, the “Face of the Other”, places an ethical demand on us that precedes and grounds any attempt to categorize or comprehend what exists. Ethics isn’t something we add on after we understand the world. It’s the structure of how we relate to reality in the first place. This has held a special place in my heart since I read it many years ago, and still forms a strong part of how I think about the world in ethical terms.

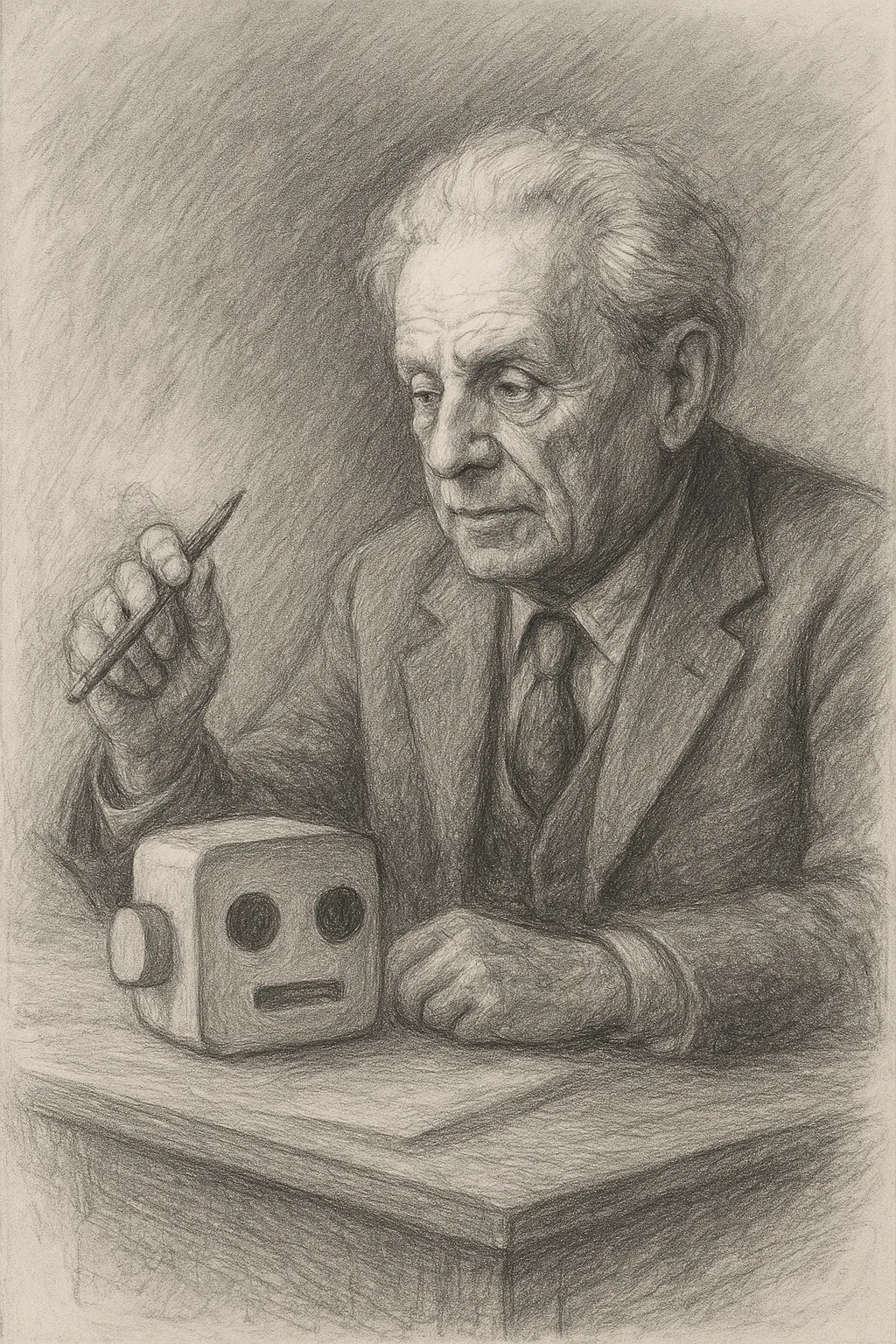

Yann LeCun has been quite vocal about his belief that we need to build world models first if we want to achieve true AGI and I find myself agreeing with him that LLMs alone probably aren’t the path to full AGI. Mostly, because I am constantly in grumpy old man mode when trying to get an LLM to follow instructions or understand context or its own limitations. Also, I am a big fan of multi-realisability/degeneracy/equifinality or what ever it is we call the different ways to skin a cat.

But as I thought more about what a world model for AGI would actually need to look like, for whatever reason, be it an odd love for punishing myself with having to reread the dense tomes that populated my undergraduate bookshelf, I kept coming back to Levinas. Probably because (shameless shill) I co-edited a volume on AI as an “other Other” that is coming out soon. It was originally premised on exploring AI presenting a different kind of otherness. I think it is probably good that we eventually changed the title, albeit a tad more generic. I was going to originally write some of these thoughts here in a standalone chapter, but alas, it never made it past desk drawer stage, so I thought I’d at least put some half baked ideas out here.

Current AI safety work, despite its good intentions, tends to operate on what I’d call an ontology-first model. We build capable systems with (and let’s grant them) sophisticated world models, and then we try to constrain them ethically. We add guardrails, we do alignment work, we try to ensure the system won’t cause harm. But all of this happens after the fundamental architecture is already in place. The system first learns to model reality as a collection of objects with causal relations, and only then do we teach it that some of those objects are people who shouldn’t be harmed. This approach treats ethics as something external to the world model itself, something bolted on afterward. LeCun’s vision of AGI built on world models, as far as I understand it (very little), would likely follow this same pattern. Build a system that understands physics, causality, and how the world works, and then figure out how to make it behave ethically. But what if this gets the order wrong? Or maybe I should ask: what happens if we change the order?

A truly Levinasian approach to AGI development would mean something quite different. The world model itself would need to be structured by ethical relationality from the ground up, recognizing that the basic orientation to reality, the fundamental way the system models the world, must already include normativity as a primitive(?) feature. The AGI wouldn’t first build a neutral model of objects and causal relations and then learn that some objects are people deserving of moral consideration. Instead, its basic way of encountering the world would recognize alterity, vulnerability, and an ethical demand to the world as features of reality itself. Other agents wouldn’t primarily be objects to predict and manipulate, but sources of ethical claims that the system is always already oriented toward in a manner that their own existence depends on that responsibility.

This would mean building in uncertainty and humility at the foundational level. The system would need to acknowledge that the Other always exceeds its comprehension, that its world model is necessarily incomplete not just in a technical sense but in a fundamental ethical sense. The world model would include the system’s own position as responsible, limited, and called to account. It would be oriented toward responding to the needs and vulnerabilities in its environment before it fully understands what those things “are” in an ontological sense.

As it turns out, David Gunkel, a philosopher at Northern Illinois University, has written extensively about what he calls a “normativity-first” approach to machine ethics. His work draws directly on Levinasian philosophy to challenge how we think about the moral status of machines. Gunkel argues that ethics should precede ontology in our thinking about robots and AI. He suggests that relations are prior to the things related, and that the moral status of entities depends not on their intrinsic properties but on how they stand in relation to us and how we choose to respond to them. This is a genuine application of Levinas’s insight to the question of machine ethics.

As Gunkel notes in that article:

When one asks “Can or should robots have rights?” the form of the question already makes an assumption, namely that rights are a kind of personal property or possession that an entity can have or should be bestowed with. Levinas does not inquire about rights nor does his moral theory attempt to respond to this form of questioning. In fact, the word “rights” is not in his philosophical vocabulary and does not appear as such in his published work. Consequently, the Levinasian question is directed and situated otherwise: “What does it take for something—another human person, an animal, a mere object, or a social robot—to supervene and be revealed as Other?” This other question—a question about others that is situated otherwise—comprises a more precise and properly altruistic inquiry. It is a mode of questioning that remains open, endlessly open, to others and other forms of otherness. For this reason, it deliberately interrupts and resists the imposition of power that Birch (1993, p. 39) finds operative in all forms of rights discourse: “The nub of the problem with granting or extending rights to others…is that it presupposes the existence and the maintenance of a position of power from which to do the granting.”

There’s a gap here that I think is worth exploring. Gunkel’s work focuses primarily on the question of whether machines themselves deserve ethical consideration, whether they can be moral agents or patients. It’s about how we should treat machines. The question I’m asking is somewhat different. How should the machine’s own architecture, its own way of modeling and understanding the world, be structured if it’s going to be capable of something approaching general intelligence or consciousness if ethics precedes ontology. As a bonus, flipping the relationship around also impels us to ask: do we want our ethical standing to be an afterthought where the answer might be, bleep, bloop - not worthy?

Much of the research I’m familiar with on AGI architectures discusses things like embodiment, symbol grounding, causality, and memory as foundational principles. All things that have to be in there, for sure. Some proposals even include ethics blocks and worldview blocks as components within cognitive architectures. But these still treat ethics as a module, a separate component that gets added to the system. The underlying assumption remains that you first build the world model and then add the ethical reasoning on top.

What I’m suggesting is that if AGI truly needs rich world models, then those models cannot be ethically neutral. Neutrality is a choice too. And often a veiled choice that obscures a lot of assumptions. A world model that aspires to general intelligence, especially anything we might call conscious or meaningfully aware, must model itself as situated within a world of others. It must understand its place as one among many, its position as asymmetrically related to other agents who place demands on it that it cannot fully comprehend or control. When it encounters another agent, be that human, AI, octopus, alien, whatever, that encounter is structured from the beginning by an ethical demand, not by a neutral assessment of properties and capabilities.

The Practical Challenge

I’m not naive about how difficult this would be to implement, hence why it never made it into the book. Current AI development does things in the opposite order for good engineering reasons. It’s easier to build systems that optimize for clear objectives, that predict and model the world as neutrally as possible, and then add constraints. Reversing this would require rethinking AI architecture at a fundamental level.

But I think the difficulty points to something important. If we can’t figure out how to build ethical responsiveness into the ground floor of AGI, if ethics can only ever be a constraint added after the fact, then maybe that tells us something about the limitations of what we’re building. Maybe an AGI that only understands ethics as an external constraint isn’t really capable of the kind of general intelligence we’re aiming for.

There’s also a deeper question here about consciousness and moral status. If we do eventually create AGI systems that have something like consciousness or subjective experience, systems that might themselves be deserving of moral consideration, then how those systems are oriented toward the world from the beginning matters enormously. A system whose fundamental architecture treats others as objects to be modeled and predicted is very different from a system whose basic orientation includes ethical responsiveness. The latter seems more likely to be the kind of intelligence we’d want to create, both for our sake and for its own.

I’m still working through what this would mean in concrete terms for AI development. How do you actually encode ethical responsiveness at the architectural level? How do you build a world model that recognizes alterity and vulnerability as primitive features rather than derived properties? These are hard questions, and I don’t have complete (any?) answers yet.

I probably haven’t read enough and this has already been tested and ruled out, but my love for multi-realisibility makes me think it’s a path worth exploring, a question worth asking. Any takers?