On Persistent Path-Dependence

And Why Values Won’t Stay Put

Will MacAskill’s recent essay Persistent Path-Dependence defends working on better futures against a common skeptical objection; that, short of preventing extinction, our actions can’t predictably influence the very long-term future because effects eventually “wash out.” MacAskill rightly argues that this is incorrect. He argues for several mechanisms that could create persistent path-dependent effects this century, particularly through AGI-related developments.

The basic assumptions that drive his essay (from §4) can be broken down into the following:

-

AGI is likely to arrive in our lifetimes;

-

AGI will drive explosive technological development;

-

This will compress many transformative developments into years or decades;

-

We’ll suddenly move from an open future to one with a clear trajectory.

Premises 1-3 seem relatively reasonable to me. Although, I am more cautious on the timeline for number 1, which I will leave for a different post and am happy to concede it for the sake of this one. My critique comes (mostly) on premise 4 and the mechanisms MacAskill describes that rely on assumptions about how values work, what AGI can or would likely do, and whose flourishing we’re measuring that deserve more scrutiny.

I think (hope) I am being honest to his work here, please go read the original for the obvious missing subtlety inherent in boiling it down to a few bullet points. There are also a number of smaller issues that don’t matter as much for my main argument here, and many things I wholeheartedly agree with and find quite compelling that I won’t touch on. It is very much worth reading.

1. Values Aren’t Fixed Parameters

MacAskill proposes several mechanisms through which values could be locked in: AGI-enforced constitutions (§4.1.1), designed beings with chosen preferences (§4.1.3), and self-modification to fix beliefs (§4.1.4). The claim, as I understand it, is that we could preserve not just power structures but specific value systems indefinitely.

For example, with AGI-based institutions he argues that a global hegemon or individual country could:

“Align an AGI so that it understands that constitution and has the enforcement of that constitution as its goal… Reload the original Constitutional-AGI to check that any AGIs that are tasked with ensuring compliance with the constitution maintain adherence to their original goals”

This would work like “conjuring up the ghosts of Madison and Hamilton” to interpret the Constitution, preserving their exact reasoning process about novel situations where the constitution “could operate indefinitely.”

Given that we are going to accept the first three premises, let’s grant that one could build an AGI that “understands the constitution,” in an incredibly rich sense. Even with this granted, it is not a system that would mechanically apply static values even given the exact reasoning processes of a constitution’s crafters.

Constitutional values, as any legal abstraction, are fuzzy by nature and the functional dependence is on the interpretive act, not the value itself. If the claim was that the AGI demanded an adherence to a pseudo-techno-originalism, this premise might hold. However, even in that circumstance, originalism almost always fails its own remit, as these values are in flux by definition.

Value interpretation requires substantive choices that are not fixed in this sense. No amount of intelligence eliminates the fuzzy judgment about how abstract commitments apply to novel situations. The agent will make choices the constitution’s authors never contemplated and relying on an original ground truth of a value (even “the exact reasoning”) is not something a constitutional agent trained on any constitutional system would actually do.

Consider the Second Amendment. Would a Constitutional-AGI consulting Madison allow nuclear weapons in every household? Assault rifles? BB guns for children? How would it deal with mental capacity, or exigencies of modern society? How would it justify any of these choices through “a ghost of Madison”? This is a long standing issue in interpretation that I am not sure is resolved because…AGI. Or At least I should say I am not sure that MacAskill’s essay has given us much reason to.

The interpretive flexibility required means the variance in substantive outcomes remains enormous. Yes, you’re constrained to justify decisions through constitutional interpretation rather than, say, parliamentary sovereignty, a dictatorial edict, or even a roll of the dice. But that’s different from locking in specific value outcomes.

I can concede it is a lock-in of a kind, a choice of one value framework over others. But even values concretized will shift internally, require balancing between competing principles, or mean something quite different under exigent circumstances.

MacAskill later argues (§5) that the US founding fathers may have successfully locked in values by enshrining liberal principles in the Constitution, enabling those values to “persist (in modified but recognizable form)” for 250+ years. But “recognizable form” is doing significant work here. Freedom and liberty as abstract categories are recognizable across time, but what they mean substantively can be irreconcilable. Freedom with slavery and freedom without slavery share a name and perhaps some conceptual ancestry, but they aren’t reconcilable substantive positions. When we say values persist “in recognizable form,” we’re often just noting abstract continuity while the substantive choices (the ones that actually matter for outcomes) vary enormously.

The path-dependence argument still holds, but calling this an example of a lock-in mechanism obscures what’s happening in delegating ongoing value revision to an AI, or won’t create disruptions (which I will address in a moment).

A similar issue appears when he writes about the appearance of designed beings (§4.1.3):

“we will be able to choose what preferences they have. And, with sufficient technological capability, we would likely be able to choose the preferences of our biological offspring, too.”

This assumes one could design a value system that is somehow uninfluenced by experience. Why would we expect this to be the case with the robust AGI we are granting here? Even if you could implant values mechanically, how do those values respond to novel situations? What happens when the designed being encounters contexts their creators never imagined? AGI doesn’t equal value completeness, and I am not sure MacAskill would argue that either, though he seems to rely on it.

This is again apparent with the argument of self-modification (§4.1.4), where MacAskill suggests:

“a religious zealot might choose to have unshakeable certainty that their favoured religion is true”

Values shift when context changes, because they are abstract categories. When I was doing voter canvassing (too long ago for me to want to admit) on California’s gay marriage Proposition 8, I spent most of the time talking to heavily religious voters. One of the things I found persuasive was not to try and change their value systems but have them rethink their content. If I stopped framing it as a threat to one or more of their sacred values and just asked about their own marriage, view of love, why they value it, etc., the antagonism often dissolved. So I kept the values recognizable, but the substantive outcome was quite different. Values that seemed fixed turn out to be responsive to how questions are framed. Even if someone could lock in their values technologically, would those locked values respond appropriately to contexts their past self couldn’t foresee? If they didn’t, would we really be talking about an AGI by any robust definition?

2. AI Beings or Human Beings?

There are a number of times where it isn’t clear if the points the essay is making are referring to future digital beings, future human beings or both. For instance, it discusses multiple mechanisms involving the creation, modification, and persistence of beings: digital immortality allowing exact preservation of values (§4.1.2), the design of new beings with chosen preferences (§4.1.3), and self-modification capabilities (§4.1.4). The claim is that unlike historical generational turnover, these technologies allow value persistence across time.

at §4.1.3:

“Probably, the vast majority of beings that we create will be AI, and they will be products of design — we will be able to choose what preferences they have. And, with sufficient technological capability, we would likely be able to choose the preferences of our biological offspring, too.”

and describing the outcome:

“the population will endorse their leader and the regime they live in, because they will have been designed to do so”

Throughout these sections, the essay slides between discussing AI beings and human beings in ways that matter for whether the mechanisms work.

On immortality (4.1.2):

“Either way, people today would have a means to influence the long-term future… The same beings, with the same foundational values, could remain in power indefinitely”

“Either way” refers to digital or biological immortality, but these are very different. For biological immortality, people’s values change over time. One might only need to think about tattoos here. Why assume values would be more stable than aesthetic preferences? Research on the “end of history illusion” posits that people acknowledge their values have changed substantially in the past but predict little change in the future. This actually makes MacAskill’s scenario more plausible. People systematically think their current values are final, so they might well choose to lock them in technologically. But the same research suggests values change in response to experience in ways we don’t predict. Even if someone locked in “I value X,” or “make me value X indefinitely”, the substantive meaning of X would shift as they encounter new situations.

For biological beings, you’d need (A) values that are genetic or implantable in some neurological sense, (B) an understanding of neuroscience to precisely implant specific values in biological brains, which seems incredibly far off even with AGI-assisted research, (C) values that somehow remain uninfluenced by experience, and (D) no intergenerational mixing when people with different designed values have children together. The essay continually references “given sufficient technology” but some of these are stretched much farther than others in their plausibility, or within a time frame that would be applicable to when path dependence would take place.

For AI beings, some of these critiques don’t apply as strongly. Persistence is perhaps an easier claim, but then we need to know are we discussing human flourishing or AI flourishing? The designed beings mechanism requires very different things depending on which beings we mean. But if “the vast majority of beings” are AI and we care about human values or flourishing specifically, do these lock-in mechanisms even affect what we care about?

3. The Stability Claim

§4.2 discusses mechanisms that reduce disruption to those in power. In §4.2.1 on extreme technological advancement, he argues:

“advanced AI systems could process vastly more information, model complex systems with greater precision, and forecast outcomes over longer time horizons… although environmental changes (such as disease, floods or droughts) have often upended the existing order, society will continue to become more resilient with technological advancement: almost any environmental risks could be predicted and managed.”

The claim is that technological maturity plus superintelligent prediction removes the disruptions that historically prevented value lock-in. Where past regimes fell to unforeseen developments, future leadership “would face far fewer disruptions.” The essay lists specific mechanisms that might accomplish this: eliminating death, controlling next generations’ values, technological maturity, superintelligent prediction and management, and suppressing rebellion.

But each faces problems. The first two are addressed above, eliminating death doesn’t eliminate value change, people’s values shift over time regardless; and, controlling designed beings’ values requires implausible assumptions about genetic or neurological implantation and values somehow remaining uninfluenced by experience.

The technological maturity claim assumes AGI stops being a source of innovation, but if AGI is genuinely intelligent and adaptable (as intelligence almost invariably requires in nature), why wouldn’t it continuously generate change? Even granting that AGI could predict disasters, stopping them requires coordination, resources, and action. If an asteroid is coming and AGI predicts it, managing the response still requires agreement on solutions and implementation. Perhaps in this scenario the AGI handles coordination and implementation too, but that just relocates the problem. The AGI still faces value judgments about which solutions to pursue and what trade-offs to accept. You can’t know in advance which intermediate goals will matter or which exigencies will demand interpretation of abstract principles. Prediction capabilities don’t automatically translate into the coordination needed to prevent disruptions.

To the fourth, suppressing rebellion assumes power-holders will submit to constraining systems, but historically they eliminate interpretive constraints when convenient. This becomes even more concrete in MacAskill’s treaty enforcement example. He suggests AGI-enforced treaties between countries, with verification that all systems comply with treaty interpretations. But if an AGI interpreter reaches a conclusion a dictator disagrees with, would they really defer to it? The first things dictators do is eliminate antagonistic interpretive systems (courts, journalists, independent institutions). Power-holders don’t voluntarily constrain themselves with systems they can’t override. Is the scenario that everyone submits to AGI’s recommendations? Are these the same power-hungry individuals who invoked the AGI to gain that power in the first place? Given the historical examples the essay itself invokes about power purging unwanted viewpoints, what happens when AGI interpretations inevitably clash with the immediate goals of those individuals?

MacAskill uses a roulette wheel analogy earlier (§4) to illustrate his point on leaning towards stability where the wheel is “wildly unpredictable while it spins, but the ball always settles into a single slot.” This assumes the “hand spinning the wheel” (technological change, environmental shocks, generational turnover) stops running the game, which for the above reasons I think is quite tenuous. Further, and to sheepishly go after the low-hanging fruit of the metaphor, the roulette wheel is a physical system with friction that naturally dissipates energy and settles. Social systems don’t work that way. Complex systems seem to do the opposite. Even the roulette wheel itself looks stable over one spin, but over its lifetime there’s ongoing change, a multiplicity of results and the eventual breakdown of the mechanism itself. Apparent stability depends on the time horizon you choose to examine. Which, for an essay discussing the allocation of deep space resources, the one spin metaphor seems a bit short.

4. Value to Whom?

The essay opens (§2) by discussing extinction risk and AI takeover. He argues that reducing extinction risk isn’t just about ensuring any civilization exists, but about which civilization exists:

“in order to believe that extinction risk reduction is positive in expectation, you must have the view that these alternative civilisations wouldn’t be much better than human civilisation.”

And:

“The view that AI takeover is bad in the long term requires the judgment that the AI-civilisation would be worse than the human-controlled civilisation”

His central quantitative claim:

“my view is that the expected variance in the value of the future will reduce by about a third this century”

Better in what sense? Better for whom? The essay never clearly specifies whose values or flourishing we’re measuring. I assume, from MacAskill’s work, he is talking about human flourishing.

One could in fact say AI takeover is bad without having to judge AI civilization as “worse.” For instance, you could value multiplicity and diversity of civilizations over any single one. Multiple civilizations might be better than one, just as multiple cultures are arguably better than monoculture. Or species diversity is better for an ecosystem and its inhabitants than a monoculture. The homogeneity and hegemony is the problem, not whether any particular civilization is “worse.”

I think this ambiguity matters for the variance claim. Variance in what? If measuring human flourishing, AI takeover might reduce variance significantly. If measuring total welfare across all beings, maybe not much variance reduction. If measuring diversity of outcomes, depends on whether AI creates homogeneity.

The mechanisms discussion inherits this ambiguity. When MacAskill discusses locking in constitutional frameworks or designed beings’ values, whose values matter? If most beings will be AI but we care about human flourishing, does locking in AI values count as reducing variance in what we care about?

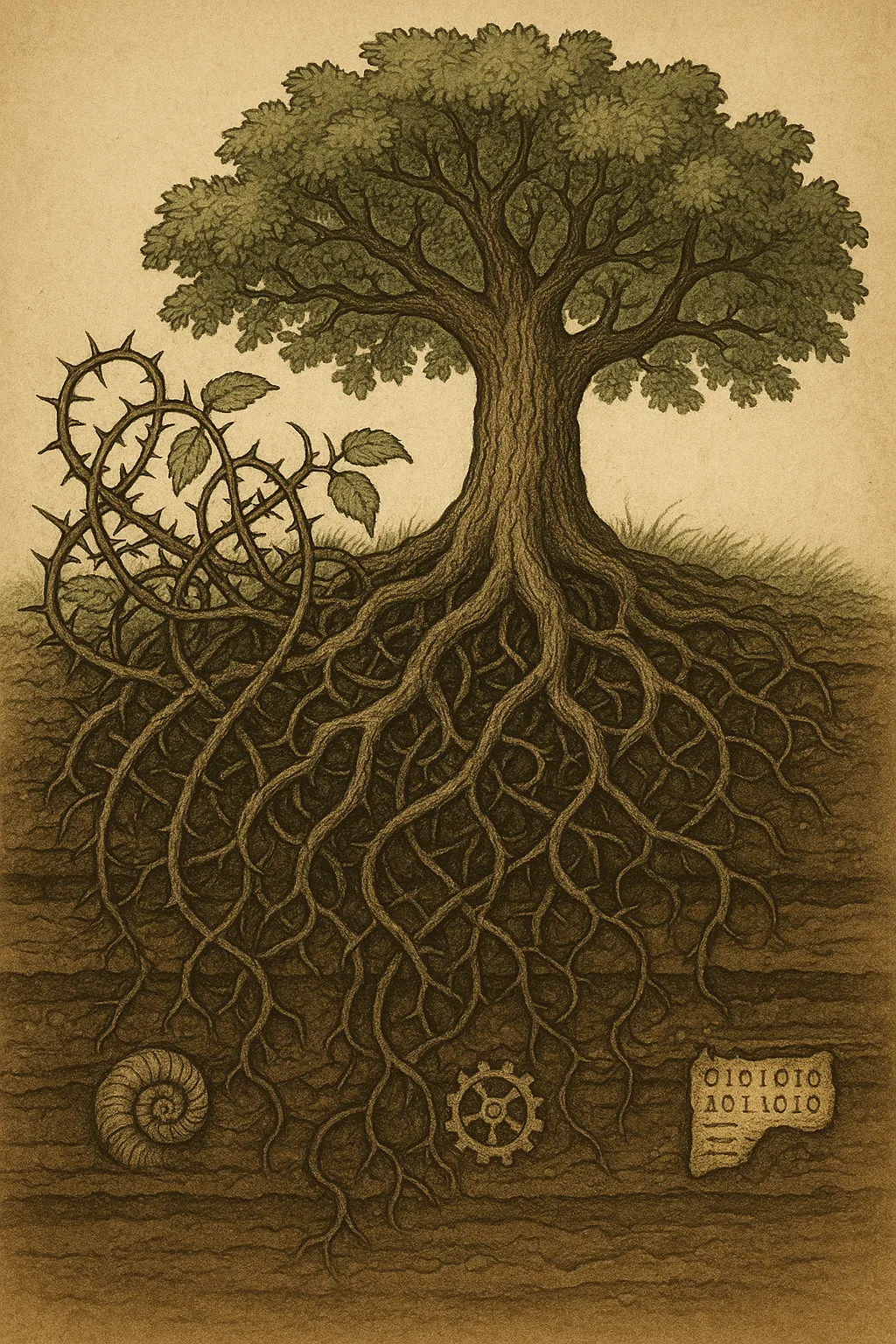

What matters more than locking in the “right” values is preserving value-deciding systems that maintain dynamism and diversity. Path-dependence, initial conditions and framework choices do matter. Chief among them for me is power concentration in its various forms in how it disrupts the potential of that dynamism to do its thing. Given this importance, I think I might even accept that a future ASI (maybe not AGI) might be able to map out a complete axiological possibility space, but I am not clear on why it would lock in any such particular space in continuity if all were available at any given time. The main driver of moral progress might not be controlling which values persist, but creating systems that allow each generation to make their own choices about what matters. Not for any overly optimistic or individualist ‘we must champion agency and self-determination at all cost!’ type reasons, but because multiple paths to good outcomes matter for the same reasons MacAskill’s essay is concerned about lock-in. Strict path dependence, where early choices determine everything that follows, is precisely what we should worry about.

Frameworks matter. But the substantive outcomes that emerge depend on interpretation, context, and circumstances that we (I think) can’t foresee. And not because effects wash out. Choices matter, but often not in the ways or with the predictability that a “lock-in” framework suggests. The variance MacAskill wants to reduce through careful framework selection might be inherent to how values organically work; that, good frameworks are precisely those that remain responsive and contextual rather than fixing principles that even superintelligent systems could preserve unchanged. A loss of control is sometimes the best choice.

Disclaimer: this post was encouraged, nay, DEMANDED by one Matthijs Maas. All letters should be addressed to he.

Edit: He has clarified. EXHORTED by.